Like many aspects of our liturgy, the curtain in front of the altar has both a functional purpose and a symbolic meaning. The curtain is closed three times during the Divine Liturgy. The first time is at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy, after the celebrant and altar servers have gone up the stairs and entered the altar area (khoran), after the priest chants the acclamation, “Ee hargee srpootyan…” (“In this dwelling of holiness…”). Behind the closed curtain, the priest offers the solemn prayer of St. Gregory of Narek, in which the priest calls upon the Holy Spirit to overlook his own human frailty and make him worthy to offer the Badarak on behalf of all the people. He then prepares the bread and wine for the Eucharist.

Meanwhile, the altar servers busy themselves with a number of tasks: carrying the chalice to the altar; presenting the bread and wine to the priest; assisting him in preparation of the gifts; returning the chalice to the side niche; lighting the altar candles; preparing the censor (poorvar) with charcoal and incense; and lining up for the procession around the church (tapor). This part of the Divine Liturgy illustrates the two practical reasons why we close the curtain: (1) to provide a private and prayerful seating for the priest while he offers prayers that concern him personally; and (2) to cover the altar area while the deacons and servers are performing practical tasks that would otherwise distract the people from prayer.

After the preparation of the gifts the curtain opens and remains open until the priest chants the invitation to Holy Communion, “Ee soorp, ee soorp…” (“In holiness let us taste…”). When the curtain closes, the priest again offers a series of private prayers to prepare himself to receive the holy sacrament. In most prayers of the Badarak, the priest always prays on behalf of all the people. In these prayers, by contrast, the priest speaks to God about his own spiritual life, sins, and needs: “Let this [Holy Communion] be to me not for condemnation but for the remission and forgiveness of sins… so that this may purify my breath and my soul and my body and make me a temple and a habitation of the all-holy Trinity….”

Once he has offered these fervent prayers, the priest himself is the first to consume his portion of the body and Blood of Jesus Christ in Holy Communion. While the curtain is closed, the choir leads the people in singing the hymns, “Der Voghormya” and “Orhnyal eh Asdvadz.”

When the curtain opens, the rest of the people come forward for Holy Communion. After all have received Communion and the priest has offered the blessing, “Getso, Der, uz-zhoghovoortus ko…” (“Save your people, Lord…”), the curtain closes again while the deacons assist the priest in washing the chalice and putting all of the liturgical vessels and Communion cloths away. The priest then puts on his sandals and crown, which he had removed earlier in the Badarak. The closed curtain shields the people from the distraction of these tasks. All of this is going on as the choir sings the post-Communion hymns of thanksgiving, “Lutsak” and “Kohanamk.” When the curtain opens, the celebrant and altar servers come down from the altar area for the concluding rites and dismissal.

When the celebrant is a bishop, the curtain is sometimes also closed momentarily at the end of the Liturgy of the Word when the deacons chant, “Mee vok herakhayeets...” (“Let none of the catechumens… draw near”). During this time the bishop removes his khooyr (mitre), slippers, banageh (medallion of the Mother of God), episcopal ring, and emiporon (omophorion, the wide bishop’s stole that wraps around the shoulders and hangs down front and back to ankle level) in preparation for the Eucharist.

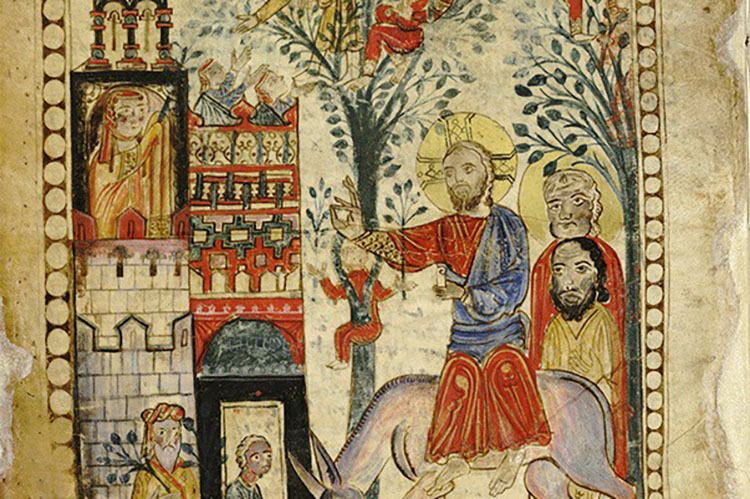

The altar curtain found in Armenian and other eastern churches developed in imitation of the curtain that enclosed the inner sanctuary of the Jewish tabernacle [Exodus 26:1-12, 36:9-17] and the “Holy of holies” of the Jerusalem temple. This has led Armenian saints and theologians to associate the opening of the altar curtain during the Badarak with our reconciliation with God the Father through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross. At the moment of Jesus’ death “the curtain of the temple was tom in two, from top to bottom” [Matthew 27:51], No longer is there a barrier between God and his faithful creatures. In the Badarak we celebrate Christ’s sacrifice that reunites us with our Creator through His loving grace.

Source: Frequently Asked Questions on the Badarak, The Divine Liturgy of the Armenian Church by Michael Daniel Findikyan.